In 2017 many companies have been humiliated by ransomware attacks. Various global attacks have cost these firms large amounts of money, with FedEx being hit for $300 million and Reckitt Benckiser $100 million. That cost is a stark reminder of how important it is to ensure the security of mission-critical data – and, perhaps unexpectedly, has deep consequences for the fibre-optic communication industry. It’s one factor raising the value of installed fibre, influencing the fortunes of companies buying up older links and driving the deployment of new ones, especially in metropolitan areas.

Security is important for Luxembourg-headquartered Colt Technology Services, as it was founded to serve financial institutions in metropolitan areas, even though it now provides backhaul communication services more broadly. Security is among many drivers of demand for fibre capacity in metropolitan areas, specifically dark fibre, explains Masato Hoshino, Colt’s vice president and head of product and technology in Asia. ‘Our customers typically use dark fibre for the end-to-end synchronisation of their mission-critical data, or to comply with regulatory requirements for secure and private routes, as well as providing recovery and business continuity capacity across multiple sites,’ he said.

‘Dark fibre offers very high levels of flexibility, privacy and control,’ adds David Pearce, Colt’s product manager for dark fibre and optical network services. ‘Our customers create private networks based on dark fibre, and have complete control over those networks. Effective network security relies on multiple layers of defence at both the edge and core of the network. By using dark fibre, Colt’s customers can achieve full network independence and physical isolation from public-facing or internet-connected networks, and by doing so help mitigate the risk of internet-borne attacks such as ransomware or malware.’

Dark fibre demand

Historically dark fibre demand has been limited to very large organisations like telephone network operating carriers, but Colt sees growing demand from other large enterprises, including major financial institutions. ‘Some customers, for compliance reasons, especially in financial services, need to demonstrate physical separation of their network,’ Pearce explains. ‘Dark fibre is a good fit for them.’

The demand for dedicated dark fibre reflects the trends eating up bandwidth across the communications industry. ‘Cloud computing is fast becoming an integral part of all business processes,’ commented Hoshino. ‘There is also greater demand for higher bandwidth to drive development of next-generation artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things, 5G wireless networks, and other digital applications.’

Connecting cloud-hosted enterprise services to the enterprises themselves is among the largest demand drivers for fibre assets in metropolitan areas, according to Jeff Heynen, director of Kagan, a group within New York-headquartered S&P Global Market Intelligence. ‘For those cloud-based services to work seamlessly, enterprises require symmetric connections to the data centres,’ he explained

Small cells and remote radio units used to support increased mobile data and video consumption are also driving demand for fibre to buildings in metro areas, Heynen adds. ‘The rise of 5G over the next decade will result in increased deployments of small cells and remote radio units,’ he said. ‘Also, there will be a heavy requirement to backhaul mobile data traffic over fibre links back to the packet core network for processing, routing, and access to network-based services.’

Finally, data centre interconnections are driving the demand for fibre. Large enterprises and data centre providers all need to connect multiple data centres within regional clusters, and to connect co-located customers with organisations located in other data centres.

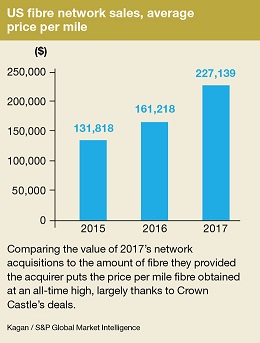

Yet it has been ‘tremendously expensive’ to put fibre assets in the ground, and only the recent upsurge in demand has caused fibre asset values to ‘skyrocket’, Heynen stresses. As such every company with fibre assets has a role to play, whether as a retail internet service provider or as a wholesaler of access to fibre facilities.

But the increasing demand has also made companies offering access to metropolitan fibre especially important. Among, these Houston, Texas-headquartered Crown Castle and Boulder, Colorado’s Zayo Group have built their businesses by buying up unused dark fibre at knock-down prices. ‘If you recall the fibre boom of the late 90s, companies like Level3 were trenching and putting in 10 fibre strands into each trench,’ Heynen remembers. ‘At the time, it was clearly overkill. But now, there is true demand for that fibre, coming from a wide range of applications and businesses.’

Zayo saw the exploding bandwidth trend prior to its foundation in 2007, according to Annette Murphy, the company’s senior vice president for fibre solutions, Europe. ‘Its growth trajectory appeared to be unalterable,’ she recalled. ‘Ten years later, driven by bandwidth-intensive communications, commerce and entertainment, data traffic is expected to continue on its growth curve.’

To develop the business, Zayo acquired companies with fibre in isolated markets, Murphy explains. ‘The consolidation approach enabled Zayo to knit together a global fibre backbone, with an extensive footprint in major metro areas, which included data centre facilities – key interconnection hubs,’ she said. ‘Since its inception, Zayo has acquired 42 companies and amassed a large network footprint. Because most routes within this network include multi-strand fibres, there can be multiple carriers and companies on one route with capacity still available. If demand exceeds supply, we will “overbuild”, adding more fibre to existing conduits, which adds more capacity on the same route. We also expand our network with new buildouts that are customer driven.’

Owners of metropolitan fibre can adopt a wide range of business models, with some only leasing access, Heynen explains. ‘Some fibre companies don’t want to get into the business of having to be regulated entities,’ he said. ‘Generally, those companies will simply lease access to their fibre facilities to companies like Comcast, AT&T, and others, who are familiar with providing end customer services that are regulated and tariffed. Others lease access and offer their own services, including content delivery networks (CDNs), video transport, data centre interconnect, and mobile backhaul.’

Customers often lease fibres for periods of 10 or 20 years, explains Rajive Keshup, a director in PwC's Telecommunications, Media and Technology (TMT) practice in New York. Enterprises and carriers using such services usually want to augment or add redundancy to their core network, he adds. The advantage of leasing is more flexibility around upgrades if there are changes in traffic loads and/or redundancy routes or plans.

If customers lease lit fibre, with networking equipment already present at each end, then that equipment determines the bandwidth they get – and the price they pay. The service provider owns and maintains the equipment, meaning the customer pays nothing for general maintenance and operation of the equipment. ‘In a dark fibre lease scenario, the provider requires the customer to provide and maintain the equipment while the provider is only responsible for maintaining the cable,’ Keshup commented.

Value model

While there are many legacy technologies in metropolitan areas, including last mile connectivity and backhaul, Zayo focusses exclusively on fibre, leasing both dark and lit options. Customers want to light, manage and use dark fibre for dedicated communications, Murphy emphasises. ‘Many customers want the control, flexibility, capacity and long-term cost savings that can come with dark fibre,’ Murphy said. ‘Others prefer a network solution that we light and deploy. We also can configure these services in a customised private dedicated network (PDN) where we lease dark fibre and also manage the network for the customer if they choose. These solutions “ride” on our dense, multi-strand fibre backbone.’

Murphy adds that networks are evolving, not least thanks to small cells, for which Zayo works with several major wireless carriers to provide fibre connectivity and turnkey solutions. ‘Fibre networks are being built to a different scale today compared to say 10 years ago,’ she said. ‘The size of cables has increased exponentially in terms of number of fibres, because it is a widely held view – and our view – that bandwidth demand will continue to increase exponentially.’

Demand for dark fibre is a key determinant of whether Zayo continues to build and acquire assets, Murphy adds. ‘Zayo has always had a fundamental belief that dark fibre fuels innovation in business better than many other network offerings,’ she said. ‘It’s why Zayo has amassed 199,550 route kilometres of fibre globally. As capabilities increase, technology changes, and demand for bandwidth increases, dark fibre is an ideal way for companies to manage their network and scale as they grow.’

For Colt, the primary focus is the very high bandwidth market focussed around data centres in metro areas, but it also serves more than 25,000 retail buildings, Pearce explains. Its metro capabilities were boosted in Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan through the acquisition of KVH in 2014, and it is now expanding in the US as well. The company also provides both dark and lit backhaul services to global wholesale telecom customers. ‘We’re very focussed on business-to-business connectivity, and especially the high-bandwidth industry,’ Pearce observes. ‘We have more on-net connected data centres than anyone else in Europe.’

In metro areas, most customers lease dark fibre, for which Colt offers a variety of lease terms. ‘It is possible for a customer to use their own WDM equipment, but it should be compliant with common standards,’ Hoshino said. ‘Colt's next-generation fibre-optic network technology focuses on a mixture of a 100G and 200G wavelength, and a 200G and 400G wavelength in the future.’

However, Colt also offers a ‘build, operate and transfer’ model. ‘We are able to build out the customer’s dark fibre network, light that network for them using the latest networking technologies and transfer that network operation and ownership over to the customer at a pace that suits them,’ Pearce said. In doing so, Colt works with equipment vendors such as Ciena and ADVA Optical Networking, most commonly deploying DWDM networks.

Combining service and innovation in this way differentiates the company’s offering, Pearce believes. ‘Increasingly we’re finding we’re able to provide valuable advice and indeed deployment of equipment on our customer’s behalf,’ he said. ‘Our customer’s end result is the benefit of a dark fibre network, but with the additional benefit of management and monitoring of that equipment by us as a service provider. With mission critical networks our customers need the in-house skills and expertise to operate those networks 24-7 and to ensure that where something goes wrong in the network they’re able to fix that really quickly. We have a very long history of managing those private networks on our customer’s behalf.’

Dig the contrast

Implicit in the name of the build, operate and transfer model is the fact that Colt actively deploys new fibre – although that doesn’t always mean digging trenches. ‘We very closely monitor the metro fibre networks for capacity, and that capacity is proactively replenished to ensure that we’ve got fibre infrastructure available where our customers need it,’ Pearce explains. ‘We replenish our fibre with as little disruption to metropolitan areas as we possibly can. Yes, where we need to reach new premises, there may be civil works required and we’re very experienced in working with local authorities all across our metros to achieve this. But we have extensive duct coverage in our metropolitan areas. So, if we’re replenishing fibre, we can pull or blow new fibre through existing ducts wherever possible.’

As such, there is ‘little chance of a shortage’ of dark fibre in Colt’s networks, Pearce says. By contrast, Heyden notes that in some areas there already dark fibre shortages. ‘Network operators can’t keep up with demand over existing, lower-count fibre strands,’ he said. ‘Also, to attain approval for a new fibre build often takes many months of reviews by public utilities commissions, towns, and municipalities.’

Keshup disagrees, echoing Pearce’s comment that there is ‘little no chance of a shortage’. ‘We see an emergence of dark fibre providers allowing for sustained purchasing power for metro fibre,’ he said, as well as lower deployment costs.

Regardless of the dark fibre supply situation, the fact that new deployments are even being discussed is a remarkable turnaround, Heynen observes. ‘I think the contrast between today’s fibre market and service/consumption demands versus what everyone hoped in the late 90s is fascinating,’ he said. ‘You could say many of those companies were visionary way back then. But, as is the case with any investment or business idea, timing is everything.’

• Andy Extance is a freelance science writer based in Exeter, UK