January of this year saw Jerry Rawls step down as chief executive of Finisar, a company he had grown from obscurity to worldwide success. He talks to Rebecca Pool about building his empire, the firm’s new CEO and a future that could include Oclaro*

What prompted you and Frank Levinson to launch Finisar in the late 1980s?

It was 1988, and we thought fibre optics was going to be a big market with big opportunities for entrepreneurs. We didn’t have any outside investors and we had to do it with our own money, which meant we had to take those nickels and stretch them into dollars. Looking back, it was a big step and my wife thought I was crazy. However, we did a lot of contract design work in fibre optics for a number of companies, which generated revenue while we worked towards the high-speed optical links that we thought the data centres needed.

Why initially focus on building high-speed networks for data centres?

Nortel, Lucent, Bell Labs and Alcatel were gigantic telecommunications companies that made optical components for the telecommunications market, and we just didn’t think we had the wherewithal with our limited resources to compete with those guys. There was virtually no fibre optics in data centres, but our view was that bandwidth requirements inside of a data centre were going to grow as the amount of data was growing. We could see the ability to move that data was going to be really important.

Who were your first significant customers?

The National Laboratories. We had already built multimode optical transceivers that ran at a gigabyte per second, so we sold these to Fermi Labs, Lawrence Livermore Labs, Berkeley Labs and CERN in Europe. These guys were building and running high-energy physics experiments and collecting a lot of data that had to be moved to a place where it could be processed and stored. The fact that we could make gigabit optical links that cost only hundreds of dollars, instead of thousands of dollars, was so important to these guys operating on a tight budget. Importantly, we could build a link that was reliable at about 500 metres, which was plenty for most of these applications, so we developed quite a following in the National Laboratories.

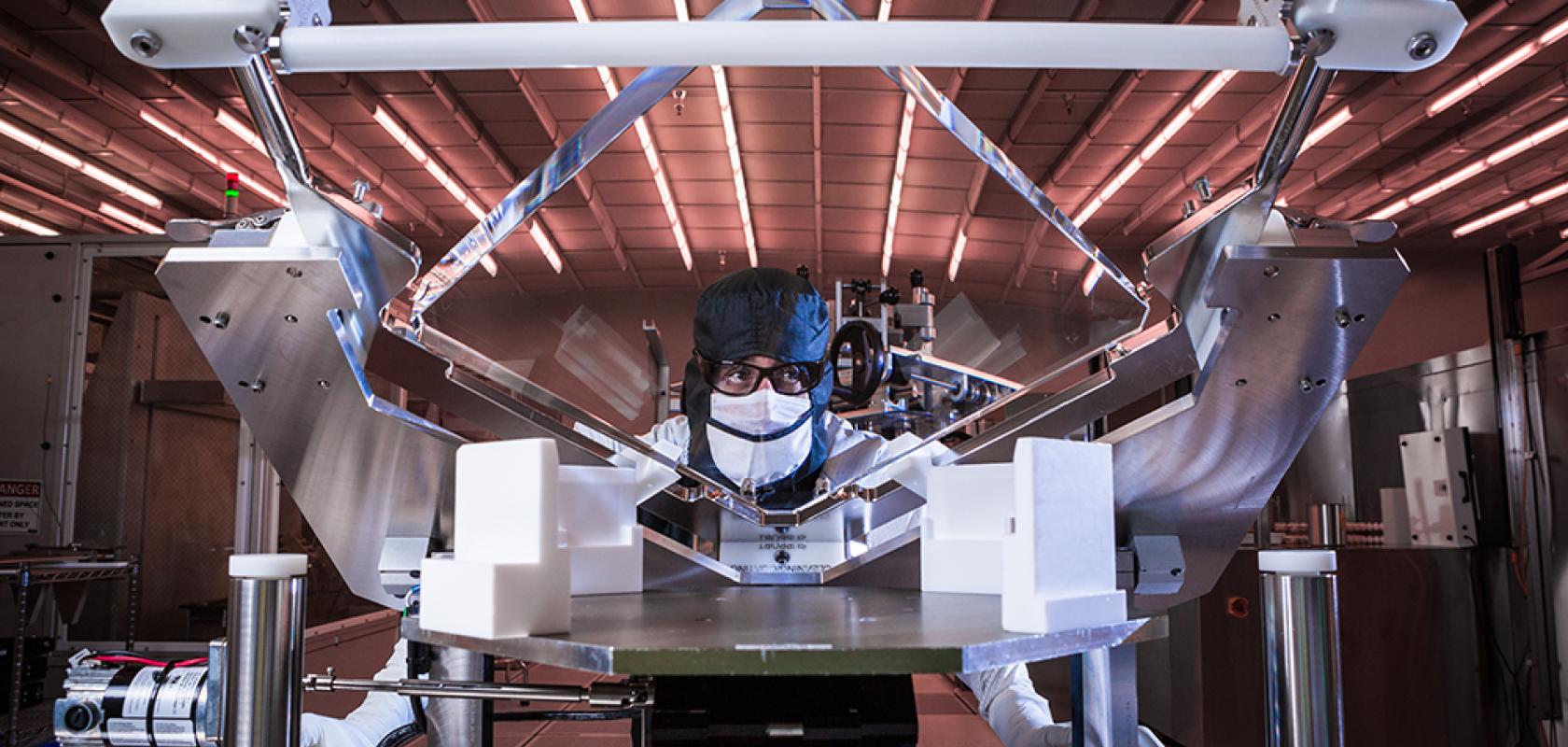

A Finisar technician examines a wafer during production at the Sherman, Texas Facility

A huge break came when the ANSI committee adopted your proposal of gigabit multimode optics for Fibre Channel Standard, instead of a singlemode protocol from IBM. What was the impact on Finisar?

It gave us credibility and it gave us a market. IBM had wanted to replace Ethernet, SCSI, Token Ring and other protocols in data centres with one very complicated, all singing, all dancing protocol that used long wavelength, 1310nm edge-emitting lasers over singlemode fibre. We explained that we could do gigabit links over multimode fibres at distances up to 500m and cut the cost of these optical links by more than a factor of 10. We encouraged [equipment vendors] to buy our demonstration board, and over the next few months we had guys from virtually every company, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, AT&T, Alcatel, you name it, visiting us. At the next standards meeting, our 850nm multimode approach was adopted and in 1998 the IEEE adopted the same physical layer definition for the Gigabit Ethernet Standard. All of a sudden, a lot of companies were interested in doing business with us, our sales grew and we went public in 1999.

On the first day of your initial public offering, stock rose by a massive 373%, what did that feel like?

We went public in 1999 because the world was outrageous. The valuations of companies were beyond anybody’s expectations and the market was so frothy that we just couldn’t turn this down. Originally, we wanted to be a private company as you have a lot of control, you don’t have to deal with quarterly earnings reports and irascible boards of directors. But on the first day of trading our market capitalisation was $4.6 billion, it was craziness. We made a lot of money; all of our employees made a lot of money and as a public company we created more than a hundred millionaires. The following year we acquired a few companies, revenues were growing and then came the crash of 2001.

Did you see the dotcom crash coming?

No. It was one of these things where all of a sudden people just had too much inventory. [At the time] we were in discussions about acquiring two companies so I called their key customers. One of the giants of telecommunications told us: ‘Yes, we have bought all of this in the past from the company, but we will not likely buy anything for the next eight years... we have so much inventory’. The other company that we were about to acquire had exactly the same thing. This was our first warning that something was going on. The problem had been back in the late 1990s; all these companies had been buying and buying as they thought their revenues would be limited by lack of supply. I remember being in an AT&T facility, which literally had its warehouse overflowing and unopened boxes of Sun workstations stacked to the ceiling in the hallway. Why? Because they were afraid they wouldn’t be able to get Sun workstations for their engineers so they bought everything they could get their hands on. It was that way everywhere in the industry.

When the crash happened, optical components sales for big industry players plummeted by more than 90 per cent but Finisar sales fell by 47 per cent – why did you fare better?

When the collapse of 2001 came, Nortel’s optical component business literally dropped 98.5 per cent, it could not survive. Alcatel was no different, Lucent the same, it was a mess. These firms were hurt so badly as they were in the telecommunications business and had competitive local exchange carriers buying from them. But we were only selling to data centres. Maybe there was some hoarding and double ordering going on, but it was nothing like what went on in telecommunications. It wasn’t easy to survive, but we did.

How exactly did Finisar survive the dotcom crash?

We realised we needed to add more value to our products and that value-add was vertical integration. Prior to the crash we had bought our components from merchant semiconductor companies... [but] we knew that we could no longer pay these companies their 65 per cent gross margins, take their products, put them on our circuit boards, resell them and make our margins. We went to National Semiconductor, hired the head of analogue design and started a semiconductor IC design group in our company. It was also a good time to buy factories because the world had too much capacity in everything. Seagate had several factories for sale, including a new factory in Malaysia. It was 250,000 to 260,000 square feet on 20 acres of land and we paid $10 million for all of it, which got us doing our own manufacturing. Vertical integration changed the nature and competitiveness of our company, and that’s what’s led to our success and how we became number one in the market.

A steady string of acquisitions followed including Honeywell vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers (VCSELs), Infineon’s 10G technology and Optium; why these companies?

Each acquisition had a strategic rationale. In 2003 we bought the Honeywell vertical cavity laser division. Honeywell had ridden through the crash but was saying: ‘Wait a minute, we have this vertical cavity laser division and we don’t want to be in components anymore.’ The division was superfluous to them, but [the VCSEL] was the key laser that went into our multimode data centre links. Honeywell was also our sole source supplier, literally, and if that facility fell into the hands of a competitor, it would have been a disaster, so we bought it. Infineon’s fibre optics division gave access to the European market. And our largest acquisition, Optium, was a total telecommunications company, so we bought it simply to have a bigger footprint in the telecommunications market.

Times have changed and with the advent of Web 2.0, data centres are probably purchasing more optics than telecommunications companies; how has Finisar adapted to this?

Well, if you think about our business over the years, we sold almost exclusively to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). The qualification standards for these OEMs were really quite severe, with Bell Labs torture-testing all of our products. Then Google came on the scene, decided that the OEMs charged too much money, and went to Taiwan to contract outside design and manufacturing companies [ODMs] to design and supply switches directly to them. Google then decided it could save even more money by buying optics directly from guys like Finisar, and this became a really big market.

What is it like trading with the Web 2.0 companies?

Well, these Web 2.0 companies tell you: ‘I don’t have to worry about where this product gets shipped, as it’s in one of my data centres... the relative humidity is always controlled, we have filtering on the power supply so we don’t get voltage spikes.’ So, the requirements on our optics were not as severe as those from an OEM, and we responded by building a series of 10 and 40G optics for the Web 2.0 companies. Today we’re the largest supplier of 100G optics to the Web 2.0 companies and we are number one in market share in the Web 2.0 market for optics. We’ve had to evolve different products, different standards, different ways of doing business, but let me tell you the purchasing power of these Web 2.0 companies is just astounding.

Web 2.0 aside, what other industry developments have been important to Finisar?

China is really exciting. Over the last decade, the Chinese market has evolved, grown unbelievably and continues to grow. We sell to Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent and the Web 2.0 companies in China, as well as selling to the big OEMs, the Huaweis, the CTEs, the FiberHomes, and the big data centre equipment companies, such as H3C. However, 3D sensing probably has the single fastest growth rate of any market we are in. You’ve read about Apple’s iPhone 10 and the use of VCSEL arrays in facial recognition. There will also be facial recognition in cars and external sensing with lidar for autonomous driving.

A Finisar technician prepares to test a set of wafers on the manufacturing floor

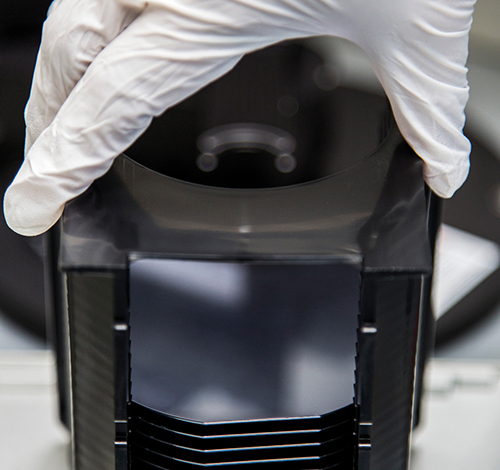

Finisar was recently awarded $390 million from Apple to increase volume production of VCSELs, including setting up a facility in Sherman, Texas. What are Finisar’s future VCSEL plans?

We bought the plant out of bankruptcy from a solar company, paying $20 million for it. We will now invest more than $100 million in the plant for equipment and facility upgrades so that we will dramatically increase our capacity to make VCSEL arrays for 3D sensing. [Manufacturing capacity] will be for 3D sensing markets and most of it in the first year or two will probably be for Apple. However, we have more than 60 other customers that are interested in fielding a system for 3D sensing. We’ve actually built custom arrays for 12 or 13 of them to put in their early prototypes of their systems. There’s going to be a lot of customers worldwide who are interested in 3D sensing.

You’ve now stepped down as Finisar CEO with Michael Hurlston replacing you. Any comments?

Michael is a very capable guy and has had a long career at Broadcom. I think Apple is Broadcom’s biggest customer, so he also has a lot of experience in dealing with Apple. Broadcom also sells its products to the guys that are number one in Ethernet switches, Ethernet switch chips, crosspoint switches, so in terms of being engaged with our customer base, Michael is very well qualified. What he’s got to do now, is understand what’s important about converting the electrical signal into an optical port.

But Michael’s an engineer, he’s got a master’s degree in electrical engineering and he will understand quickly what is involved there. I told our board five years ago that I wanted to retire in five years, they took me at my word and we went off six months ago to look for a replacement and we’ve found a good one. And for me it’s the right time, I’m 73 years old and I’ve worked a few years longer than I ever thought I was going to work, but I’ve had a lot of fun doing it.

Will Finisar ever acquire Oclaro?

I know Oclaro well, I know their CEO well, I think they’re a good company, they have good technology and is it possible that at some point in time we would join forces? It’s possible. I can’t predict that. I think that consolidation could be positive for our industry because we have a lot of competitors and if we could combine some of the efforts of those competitors, I think the whole industry would be more efficient. I think we duplicate each other’s R&D too much today.

Technology development is expensive; will Finisar spend significantly on research and development in the future?

Well there’s no question, our success depends upon us having every generation of technology adopted in our products. We had to make one gigabit optics when the world needed one gigabit optics, 10G optics when the world needed that, 40G, 100G, and today our labs are working feverishly on 400G optics that will be deployed in a couple of years. If you’re a technology company and you miss any of those technology waves it can put you out of business. But if you hit them early and you hit them with good products, you can surf down that wave and gain a lot of speed.

Looking back on the last 30 years, would you do anything differently?

I would say one of the things we didn’t do is we didn’t build a presence in China fast enough. We have more than 6,000 people in China today, we have our international purchasing office in Shenzhen which is almost 200 people, we have an R&D site in Shanghai which is over 400 people, engineers there doing R&D, and then we have about 5,000 in Wuxi an hour and a half from Shanghai in a beautiful new manufacturing building that we built there. But the Chinese market has evolved very rapidly and, though we do a lot of our development in China today, as well as manufacturing, if I had to go back and do it over again we would have invested in China probably earlier than we did and put more emphasis on doing R&D in China.

* Since this interview was conducted, Lumentum announced its acquisition of Oclaro's outstanding common stock in a $1.8 billion agreement.