For a long time, data centre operators turned to original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) as the obvious source for their cables and optical modules. But OEMs are losing their magical grip on the optical connectivity market, says ProLabs, a UK-based supplier of ‘compatibles’.

Compatible products can include optical transceivers, as well as cables that have transceivers built onto each end, such as direct-attach cables and active optical cables. The transceivers can vary in speed, configuration and form factor, depending on the application, but most are built according to industry standard specifications, designed to ensure interoperability.

But interoperability is not a given. As part of those standards, transceivers have some intelligence built-in, in the form of a memory chip or microprocessor that holds product information and digital diagnostics. OEMs typically add a product key code to the transceiver, so that if the code is not present when the transceiver is plugged into their equipment, the transceiver will trigger an alarm and may not work. This prevents other manufacturers from selling into that market, creating vendor lock-in.

ProLabs thinks the market is ripe for change. In a company survey conducted at the European Conference on Optical Communications (ECOC) in 2014 with more than 120 respondents, ProLabs found that quality, price, and service were ranked as the top three most important factors when purchasing fibre-optic components. Only 14 per cent of respondents said they considered brand names to be a top three concern. The detailed results paint a fuller picture: 98 per cent of respondents ranked quality as one of their top three priorities when purchasing fibre optics, with 89 per cent highlighting price in the top three. In other words, customers want a low price, but they are not willing to compromise on quality.

That’s where ProLabs comes in. ‘Most people buy from the main vendors. They don’t realise that they can buy the equivalent product – often of higher quality, believe it or not – and at lower prices,’ explained ProLabs’ chief executive Nick Moglia.

Moglia hopes the company can emulate the success of Kingston Technology, now the world’s second largest supplier of memory chips. Yet, when Kingston was founded back in 1987, there were no third-party suppliers; everybody bought their memory from computer manufacturers, who had the market locked down. Kingston differentiated itself from its competitors through 100 per cent testing, so that quality was guaranteed.

Before the compatibles market existed, prospective optical transceiver purchasers had two options. They could buy the expensive OEM module, with the security of knowing they were buying a part whose quality was backed by the manufacturer – although counterfeit modules are a problem in their own right, as they are with any high-end branded product. Or they could buy a cheap, generic part from a Chinese vendor and take the risk that it wouldn’t work at all. ProLabs and other compatible vendors think there is a productive middle ground.

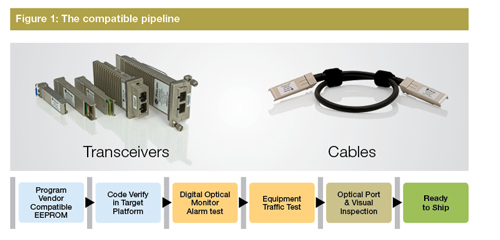

Their approach is simple: reverse engineer the product, locate a reliable supplier, then bring the blank transceivers into their own warehouse, where the code is added and the transceivers are tested to make sure that they actually work (see Figure 1). Compatible vendors then sell the transceivers for much less than the OEM would charge, typically up to 70 per cent less.

The quality assurance process starts even before the blank transceivers arrive at ProLabs’ warehouse. Head of operations, Simon Hopcraft, heads out to visit their main suppliers to carry out a mini audit. ‘You get sense from the people on the ground, about how they look after their product, he said. ‘Are they really serious about making a good quality product that could go anywhere in the world, and that we are proud to put our name on.’

Once in ProLabs’ facility, the transceivers are quality checked at multiple stages: when they arrive, when they’re coded, and again before they are shipped. The most critical check is to plug the transceiver into a representative OEM system in the lab, to verify that it operates correctly, and that data traffic passes without errors. Engineers then check all the diagnostic monitoring functions on the transceivers and finally, before it ships, they perform an optical port and vision inspection.

‘This is a real differentiator between what we’re doing and what you’ll find [at other suppliers] in the compatibles market space. Some people will literally buy in from China and ship it out again, without knowing whether it’s working or not,’ explained Christian Rookes, vice president of product management at ProLabs.

Senior test and applications engineer David Knight checks that ProLabs compatibles work in the intended platform

Over time ProLabs has built up knowledge of all the different vendor equipment codes and the way they operate. The company now has an extensive range that it has developed to work with 20,000 pieces of equipment from more than 50 OEMs, including Cisco, Dell, Hewlett Packard, Intel and Juniper. ‘This kind of applied quality checking means ProLabs can engage with some very large telecoms companies, which is not something that the compatibles market can do in general,’ claimed Rookes.

With the supply chain in place, ProLabs now believes its main challenge is to educate the customer about the compatibles market. ‘We often get asked by customers, is this dodgy, is this illegal? It is absolutely not,’ said Rookes. When you buy a replacement part for your car, there is no need to buy the expensive manufacturer branded part; the end customer can choose from a range of aftermarket suppliers, usually at much cheaper prices. The optical module market should offer the same degree of customer choice, he contends.

Some customers may be concerned that the use of third-party products could invalidate their warrantee, but that’s not the case according to ProLabs (see White Paper: Discovering the Truth Behind Transceiver Warrantees). ‘Cisco has never put that in writing,’ Rookes commented. Naturally Cisco and other manufacturers don’t want customers to buy outside their own sales channel, but there is no real obstacle to prevent customers from buying third-party products. In Europe, any warrantee tie-in, whether implied or explicit, would be illegal, according to ProLabs.

The benefits of compatible parts can also include functionality that’s not available from the original manufacturer. For instance, ProLabs offers parts for legacy systems that are no longer supported. It also provides multi-coded transceivers that have been coded to work with three vendors: Arista, Cisco and Juniper. This helps data centre operators economise on internal processes and storage space, with just one part number to manage instead of three.

ProLabs can also offer direct-attach cables with separate coding at each end, allowing them to be plugged into equipment from different vendors to create true interoperability. With this in mind, the company has partnered with Mellanox to create a range of products that allow Mellanox switches and network interface cards to be connected to non-Mellanox devices. ‘With our knowledge of coding, we can tell you if it is possible to combine OEM [equipment],’ said Rookes.

Also on the product roadmap is ‘remote coding’, where customers will receive a coding device that allows them to add the code to the transceivers on-site at a later stage, once they know which piece of equipment it will be connected to.

Closing the technology gap

ProLabs’ roots stretch back more than a decade, when it was part of international IT distributor Zycko. Seeing untapped potential in the compatibles market, ProLabs became independent in 2013 and has embarked on an ambitious expansion plan. ‘We spent the last year investing heavily in premises, people and product line development,’ explained Rookes.

One of ProLab’s first moves after going independent was to hire Giacomo Losio, former lead optical design engineer at Cisco, as its head of technology. Losio helped to develop the key building blocks of Cisco’s optical modules, including the tunable XFP, MLSE 10Gb/s transponder, and 40G coherent optical module – experience he can use to guide ProLabs as the company looks to broaden its product range to include the very latest designs.

The only difficulty with the compatibles business model can be the time it takes to bring out new products; sometimes two years can pass from when the OEM product reaches the market before the compatible supplier has a suitable replacement part. ‘Closing the technology gap means working with our partners to gain early access to technology,’ said Rookes.

The compatibles market is catching up; product development that previously took two years can now be compressed into months. ‘They’re about to release a new 10G [copper] standard and I believe we’re only six months behind the market,’ said Rookes. The company is keeping a close eye on emerging technologies like silicon photonics, next-generation 100G and 400G.

ProLabs also needs to have quick reactions when it comes to shipping orders; it aims to ship 90 per cent of transceivers out to customers within 24 hours of the order being placed. That’s one of the reasons that the company recently moved to a purpose-built facility in South Cerney, UK, with 8,800 square feet of warehouse space. Customers can enjoy next-day delivery, instead of waiting 6–12 weeks to receive parts from OEM suppliers.

To service customers outside Europe, ProLabs has partnered with a number of distributors. ‘When I started we had three distributor partners in the UK and one in the US. Now we are truly global, we are everywhere except Russia – and that’s a big differentiator compared to our competitors,’ Moglia asserted.

Moglia is building up the company because he is convinced that the market opportunity could be massive; after all, the market for optical transceivers was worth $5 billion in 2014, according to market research firm LightCounting. Already, the privately owned ProLabs is shipping around 17,000 transceivers per month, and increased its turnover to £25 million in 2015. ‘The building blocks are in place; we are well placed to achieve those aspirations’, he concluded.